Violet Oakley was truly a citizen of the world; as a muralist, illustrator, portrait painter, author, designer, and visionary, Violet Oakley stood out amongst fellow female artists of her generation. Her devotion to art and the belief that it was not only for “the select few” was made apparent through her involvement in political activities, which mainly focused on international issues of world government and disarmament. With such devotion to art and its place in politics, Violet transcended conventional roles of painting and portraiture and by 1911 she had become the only American woman to have established a successful career in mural art.

An Artistic Lineage

Violet Oakley [b. June 10, 1874] was born into a third generation of amateur and professional artists. Her father, Arthur Edmond Oakley, was a successful businessman who held a great interest in arts; as a young woman, her mother, Cornelia Swain, taught drawing and painted portraits in San Francisco; her elder sister, Hester, was a writer and illustrator; aunts Julianna and Isabella Oakley studied painting in Munich; both grandfathers were members of the National Academy of Design. So, it came as no surprise when Violet began to show interest in the arts and her early efforts of expression were highly encouraged. With pencil or brush in hand she filled numerous sketchbooks from childhood well into adulthood that captured daily events, family outings, concerts, and landscapes.

Women Playing Piano: page from Violet Oakley's Sketchbook

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania boasts around 140 of these personal sketchbooks in its vaults. (Violet Oakley Sketchbooks Call Number: Collection n. 3336)

Formal Education

Enchanted by the stories her aunts wrote in letters home from abroad, Violet started to live vicariously through their tales of adventure and art in foreign lands. This prompted her to start a more formal education in the arts. However, her training was quite sporadic in the beginning. In 1894 she traveled with her father to New York City to study at the Student’s Art League, then in 1895 while on an extended family trip to Paris she enrolled at the Academie Montparnasse to study under Edmond Aman-Jean and Raphael Collin. In 1896, while still in Paris, her father became ill and the family returned for medical treatment in Philadelphia. Violet entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to study under Cecilia Beaux, Joseph de Camp, and Henry Thouron. She would leave to study at Drexel a year later, but in 1913 she returned to PAFA to teach a class in Mural Decoration and was the only other woman besides Cecilia Beaux to teach there until the 1950’s.

After her year at PAFA Violet decided to change focus and left for the Drexel Institute School of Illustration to study under Howard Pyle, the most celebrated illustrator of the late nineteenth century. Pyle was known for his charismatic nature and generosity as an educator and was a significant inspiration to aspiring artists. He played a particularly large role in Violet’s education and was a tremendous inspiration to her. She admired him for his skill and versatile drawing style and throughout her career similarities in their aesthetic became apparent.

Commissioned Work

Between the years 1896 and 1906, under the encouragement of Pyle, word of Violet’s skill began to spread and she undertook numerous commissions. Violet was contracted to illustrate for numerous magazines such as Harper’s, Century Magazine, and Everybody’s Magazine. In 1900 All Angel’s Church in New York City approached Violet to decorate their church. She designed for them five lancet windows, a glass mosaic altarpiece and two large murals for the Apse. These two paintings were the beginning of Violet’s established career as a muralist.

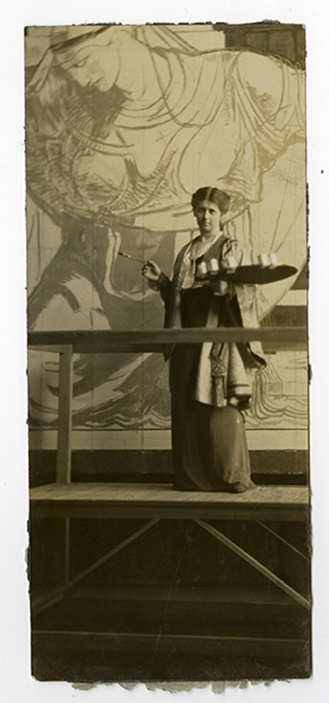

In 1902 Joseph Huston, the architect of the new Pennsylvania State Capitol building in Harrisburg decided “at least one room should be decorated by a woman” and commissioned Violet to paint 13 murals for the Governor’s Reception Room. This would be the first time in American history that a woman was awarded such a commission in a public space. Violet decided the land of William Penn was a good place to begin her studies. She felt the imagery in the Capitol building should reflect ideals promoted by the founder of Pennsylvania, so Violet and her mother sailed to England and studied the history of the Quakers and of William Penn. Violet’s studies of the Quaker doctrine heavily influenced her personal outlook on life; she stated, “In time I became so impressed by the belief or testimony of the Quakers against carnal warfare that this idea, the victory of law, or truth over force, became the central idea of my life”. Violet would have another opportunity to exercise this new found doctrine. In 1911 Edwin Austin Abbey, the original artist commissioned to decorate the Senate and Supreme Chambers of the Capitol building, passed away before he could begin the work and Violet was approached to fulfill the rest of Abbey’s contract. From 1911 – 1927 she worked tirelessly on both rooms, taking the opportunity to continue to develop ideas found in the Governor’s Reception Room.

Violet Oakley with mural, photograph, undated

Art and Politics

Immediately after the completion of the Supreme Court murals, Violet left for Geneva, Switzerland to document the League of Nations. Oakley interpreted the creation of the League of Nations as an extension of William Penn’s ideals (as well as her own) and found herself a self-appointed ambassador. Violet’s involvement in this political event caused her to see a direct relationship between Geneva and Philadelphia and envision a “great Suspension Bridge connecting Penn’s City of Brotherly Love and the City of Geneva”. During the years 1927 to 1929 Violet created numerous portraits of the League’s member-delegates and other dignitaries for a Philadelphia newspaper, many of which were later turned into widely exhibited portfolios. These portfolios embodied Violet’s hope for a world where all nations could live together in peace. The originals were later presented to the Library of the United Nations in Geneva. After all of her involvement, it caused Violet great dismay when she learned of the United State's refusal to join the League.

Leage of Nations Delegate: page from Violet Oakley's Sketchbook

Violet felt politics was not an inappropriate activity for an artist. She strongly believed that the world’s problems are not to be left solely to politics and economics – that the attempt to create harmony in the world is in itself a work of art in which everyone has a part to play. Violet found a way to communicate this idea in a more accessible manner through two portfolios of color reproductions of all the Harrisburg murals along with a detailed explanation of them in a personally designed hand-lettered text. The Holy Experiment – William Penn’s term for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1682, depicted the images found in the Governor’s Reception Room and the Senate Chamber. Law Triumphant, the sequel, contained reproductions found in the Supreme Court Room and portraits of delegates who participated in the League of Nations (1933).

Violet Oakley’s collective work represents a lifelong pilgrimage and quest to help establish peace and harmony throughout the world. She embraced this as her “sacred challenge” with passion and dedication until her death at the age of 86, at her home in Philadelphia, 1961.