The following article was written by HSP volunteer Randi Kamine and is being posted on her behalf. Many thanks to Archival Processor Megan Evans for helping prepare these articles for publication.

One of the interesting things about processing a collection at HSP is that one never knows when a significant document might unexpectedly show up. For instance, four letters in Benjamin Franklin’s hand were brought to light when a finding aid was recently written for the Read family letters (Collection 0537). All four were written to John Ross, a prominent Philadelphia lawyer and frequent correspondent of Franklin’s. Ross was half-sister to Gertrude Ross Read, the wife of George Read of this collection who was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Ross and Franklin had a political relationship as well as a friendship. Both were active in the politics of the time, especially in the rivalry between the Quaker and Proprietary parties that were fighting for control of the Pennsylvania assembly. Both Ross and Franklin were in support of the Quaker party and in opposition to the Proprietary party.

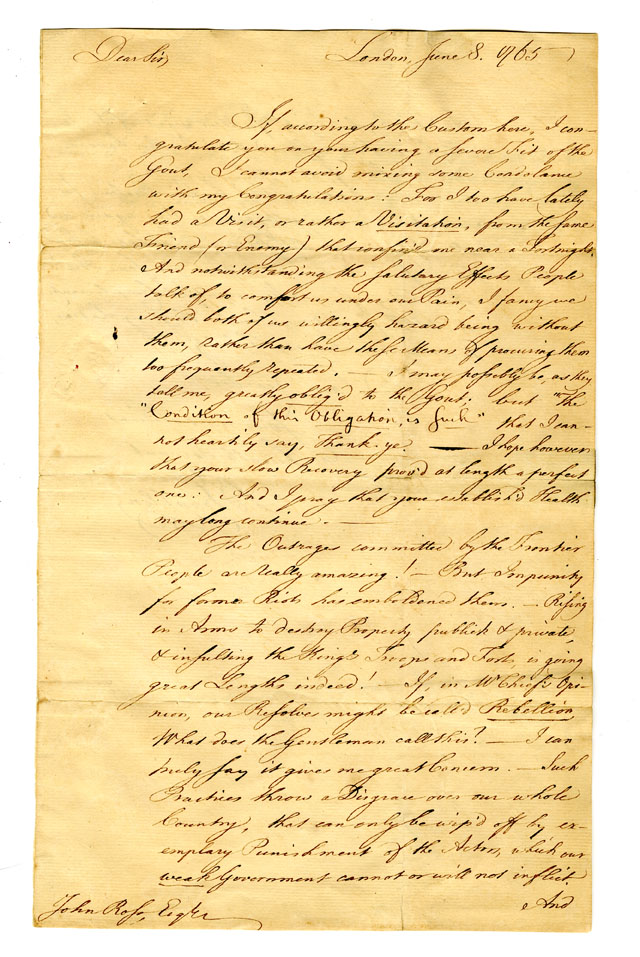

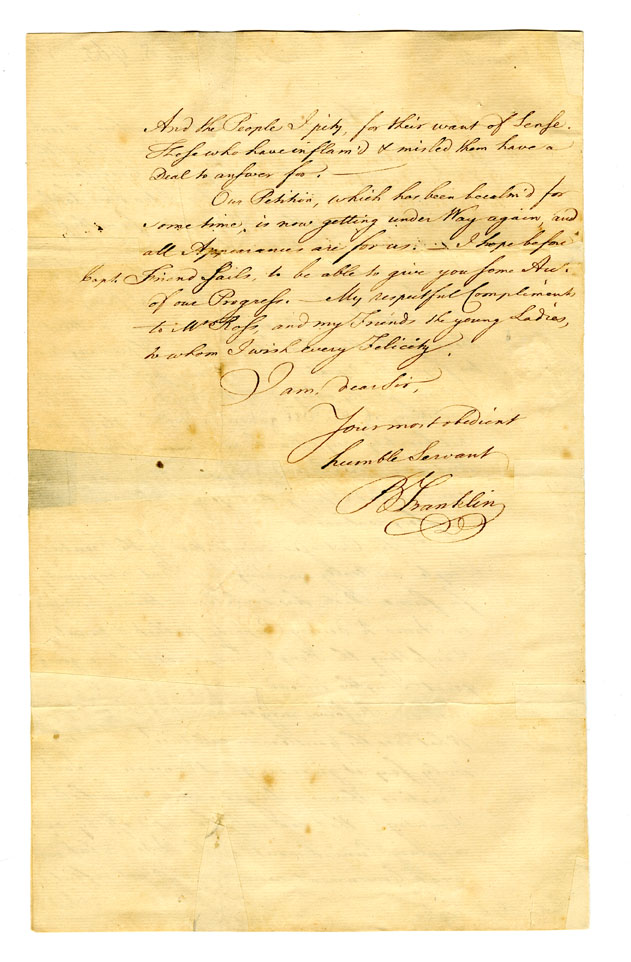

Franklin is well known as being a prodigious correspondent. However, “running into” these letters, without expecting to made processing the George Read papers a bit of an adventure. The four Franklin letters were written from London. They are dated February 14, 1765; June 8, 1765; April 11, 1767; and May 14, 1768. Valerie Lutz, Head of Manuscripts Processing at the American Philosophical Society is familiar with Ben Franklin’s handwriting and believes them to be authentic. In addition, the Franklin Papers’ Project at Yale has attributed these letters to Franklin. Although the Yale Project notes that these letters are in the possession of HSP, until the Read Family Papers were processed, it was not generally known where they were located.

Fortunately for the researcher, there is a plethora of information on Benjamin Franklin that is owned by HSP. In 1965, the Society entered into an agreement with The Library Company of Philadelphia (LCP) by which LCP administers the Society’s pre-1820 imprints. Many of HSP’s Franklin-related materials are housed right next door at The Library Company. A bibliography at the end of this essay will point interested readers to some of our extensive Benjamin Franklin and early Pennsylvania history documents.

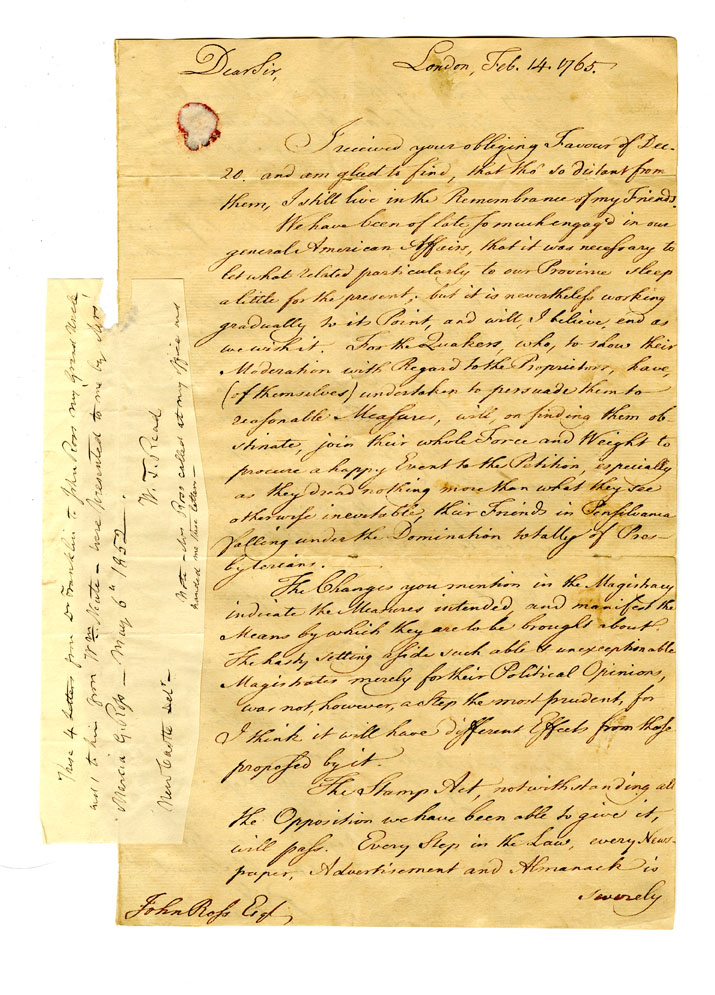

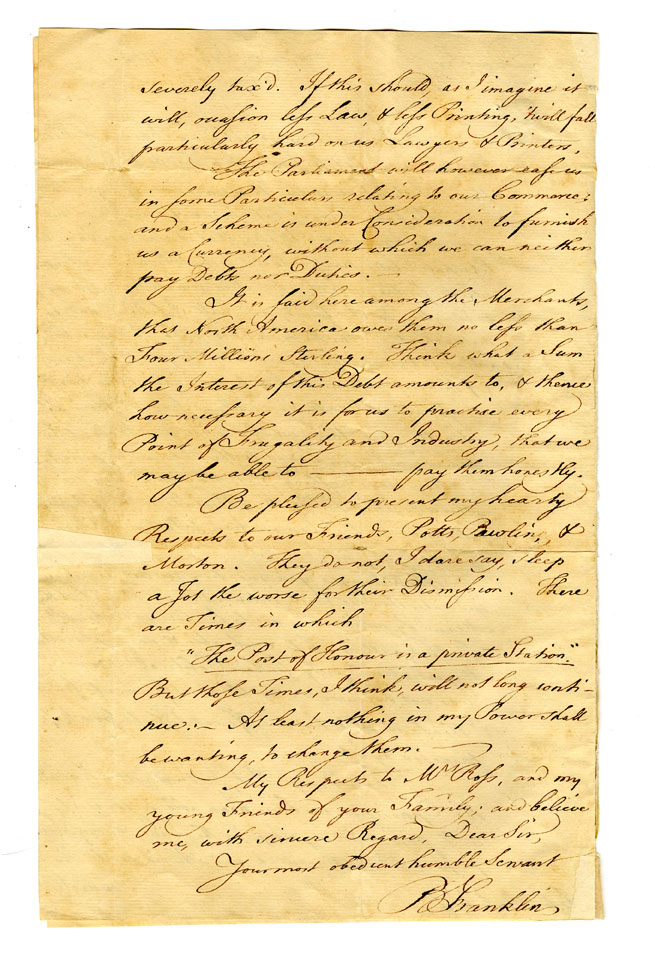

Benjamin Franklin to John Ross, February 14, 1765

In the letters found in the Read family letters, Franklin addresses events happening in Philadelphia during his time away in London -- and the years 1765 to 1768 were dynamic ones for the city. Although he writes in the February 14 letter, “We have been of late so much engag’d in our general American Affairs, that it was necessary to let wait what related particularly to our Province sleep a little…,” Franklin nonetheless expressed his insights and opinions on the political machinations that directly affected Philadelphia.

In December 1764, Franklin was sent by the Pennsylvania assembly to England with a petition for King George III. The petition, penned by Franklin, asked that Pennsylvania be made a Royal colony rather than remain a proprietary province. It is this petition that Franklin refers to in the first letter of the four.

The Quakers had dominated the Pennsylvania Assembly since the 1701 Charter of Privileges. However, the mid-1750s saw power shifting away from the Quakers. By 1764 the Assembly had many non-Quaker leaders, was only nominally associated with the Society of Friends, and no longer predominately pacifist. This was in part due to the Proprietary party which primarily represented the special privileges of the proprietors as landlords and was the political rival of the Quaker party. Franklin, although not a Quaker, was aligned with the Quaker party. He therefore writes about the desire for a “happy Event to the Petition,” and the “dread of the Friends in Pensilvania falling under the domination of the Presbyterians” (the Proprietary party was sometimes referred to as the Presbyterian party). Although Franklin continues to report on the petition in all four of the letters in this group, in the end, both the Proprietary and Quaker parties disappeared as the Revolutionary struggle manifested, making the petition moot.

Many of us are familiar with the Stamp Act as a catalyst of the American Revolution. In March 1765 the English Parliament imposed a stamp duty on written documents that included newspapers, deeds, contracts and many other legal documents, as wells as ships’ manifests. Franklin was correct when he predicted in his February 14, 1765 letter above, “The Stamp Act, notwithstanding all the Opposition …will pass.” While in London, Franklin used his social connections and the English press to try to influence the government to repeal the tax. And the Stamp Act was, in fact, repealed in March 1766. Shortly before the repeal, Franklin went before the House of Commons to argue against the tax.

HSP has a copy of a transcript of Franklin’s testimony before the British House of Commons (see bibliography below). It is a must read for those interested in getting a feel for the experience. There is an interesting insert with the HSP transcript that is undated and not attributed:

"The appearance of Franklin before the House of Commons was the highpoint in the parade of English merchants, colonial agents and visiting Americans advocating the appeal of the Stamp Act. Hoping to achieve immediate repeal, Franklin minimized American opposition and conveyed the idea that external taxation would be accepted."

One must read the transcript personally to determine if Franklin succeeded in minimizing American opposition to the tax, and to determine how much influence Franklin might have had in the decision to repeal the tax.

Benjamin Franklin to John Ross, June 8, 1765

On a more personal level, in his second letter dated June 8, 1765, Franklin discusses gout, a malady from which both he and John Ross suffered. Franklin was one of its most famous sufferers, having written a dialogue between himself and “the Gout” in his well known satirical style. That essay was written in 1780, well after the letter in the Read family letters was written. However, Franklin’s sardonic humor shows through in this earlier letter to his friend. At the time this letter was written, pain caused by the condition was thought to increase resistance to the disease. Thus, Franklin made light of the obvious discomfort he was enduring. Franklin then discussed more serious matters. In the decades before the American Revolution there was great unrest in the western frontier of Pennsylvania between settlers and Native Americans. The massacre of twenty Conestoga Indians (also known as the Susquehannock) near Lancaster by the Paxton Boys in December 1763 is one of the more well known actions perpetrated by a vigilante group in American history. The Paxton Boys were never identified or punished for their murders. By 1765, the frontier in Pennsylvania was close to anarchy. There was an intense battle between the Scots-Irish immigrants and the Native Americans over land. In a letter to Franklin dated May 20, 1765, John Ross wrote, “…Another affair has happen’d of a very Extraordinary Nature, Even His Majestys troops have been attack’d and fired upon… .” Quakers, with whom Franklin was aligned, condemned the continuing violence, although little could be done to prevent it. Franklin writes in his June 8, 1765 letter (perhaps in answer to the letter Ross wrote to him on May 20), “The Outrages committed by the Frontier People are really amazing! But Impunity for former Riots has emboldened them.”

Franklin notes that the petition to end the proprietorship, written about in his February 14 letter, “has been becalm’d,” no doubt due to the preoccupation of colonial agents with the impending Stamp Act, the illness of the King during the first months of 1765, and other important business that the King’s government was attending to. The note at the bottom of the letter is in Ross’s hand, and appears on an otherwise blank page of Franklin’s letter. Apparently Ross included an extract from “governor F” and discussed further negotiations concerning the Proprietors.

Join us next week for Randi's analysis of the third and fourth Benjamin Franklin letters from the George Read family letters.

****

Bibliography

It’s true that many documents mentioned in this essay can be read online. I posit, however, that it is enlightening to read original or contemporaneous documents. Seeing the handwriting of the author, or a transcript printed shortly after an event, gives the reader a sharper sense of the time the document was written. And for some of us, it’s just plain fun.

HSP documents:

Read family letters (Collection 0537).

Ralph L. Ketcham, “Benjamin Franklin and William Smith: New Light on an Old Philadelphia Quarrel,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 88 No. 2 (April, 1964), pp 142-163. [Call number: UPA F 146 .P65]

HSP documents at the Library Company of Philadelphia (LCP):

Great Britain Parliament, 1766 House of Commons. The examination of Doctor Benjamin Franklin: before an august assembly, relating to the repeal of the Stamp-act &c, Philadelphia: Hall & Sellers, 1766. Call number: Rare/AM 1766 FRA 51952.0.3.

For information on the Proprietary party v. the Quaker party:

Galloway, Joseph. The speech of Joseph Galloway, esq, one of the members for Philadelphia County…, Philadelphia: W. Dunlap, 1764. Call number: Rare/AM 1764 Gallo 8605.0.10.

Hunt, Isaac. Looking-glass for Presbyterians: or a brief examination of their loyalty, merit and other qualifications for government…, Philadelphia: Armbruster, 1764. Call number: HSP in LCP/AM 1764 Hun Ar64 L87.

Williamson, Hugh. The Plain-dealer or a few remarks upon Quaker-politicks, and their attempts to change the government of Pennsylvania:…, Philadelphia: A. Stewart, 1764. Call number: Rare/AM 1764 Wil.66 984.0.1.

For information on Franklin’s letters:

The American Philosophical Society and Yale University. Digital Edition by the Packard Humanities Institute. http://franklinpapers.org/franklin//

The Papers of Benjamin Franklin Project at Yale University. http://franklinpapers.yale.edu

The National Archives: Founders Online: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-12-02-0083 [This site is very helpful in interpreting Benjamin Franklin’s letters. It is easily searchable and includes letters written to and from Franklin.]

Other documents:

John Ross to Benjamin Franklin 5/20/1765: http://smithrebellion1765.com/?page_id=393

For information on gout at the time of the letters:

Copland, James, A Dictionary of Practical Medicine, Volume 4 (Longman, Brown, Green:1858)